Babesia gibsoni is a tickborne protozoal blood parasite that causes hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, lethargy, and splenomegaly in dogs

TEXT: Yung-Tsun Lo D.V.M., Ph.D, Bioguard Corporation

Canine babesiosis occurs worldwide and results from infections with a variety of Babesia spp., tickborne hemoprotozoa. Based on their morphology, Babesia spp. are classified into the small Babesia group (trophozoites of 1-3 μm; including B. gibsoni, B. microti, and B. rodhaini), and the large Babesia group (3-7 μm; including B. canis, B. volgeli, B. rossi, etc.). The distribution of the canine Babesia species is greatly affected by the presence of tick species in the area. B. gibsoni has been recognized as an important pathogen that affects dogs of all ages in Asia, Middle East, Africa, Europe, and many areas of the United States.

The Transmission

The primary transmission mode of B. gibsoni to dogs is by infected ticks during feeding, and this transmission requires 2-3 days. The transmitted tick vectors include Haemaphysalis bispinosa and H. longicornis (asian longhorned tick or cattle tick), and possibly by Rhipicephalus sanguincus (brown dog tick) in different countries. In addition, transmission can also occur through blood exchange when dogs fight or transfusion. Transplacental transmission (to unborn puppies in the uterus of their mothers) is also thought to occur because B. Gibsoni has been detected in puppies as young as three days old. With the expansion of tick habitats, the spread of parasites into new geographical areas has been an increasing problem worldwide.

The Symptoms

The disease is more severe in young dogs, immunosuppressed dogs, heavily parasitized dogs, and when there is exposure to a virulent strain or concurrent infection. Infected dogs may exhibit either peracute, acute, subclinical or chronic signs of disease. Clinical signs present are ambiguous, which includes depression, lethargy, fever, weakness, vomiting, pale gums and anorexia. However, other specific signs include dark colouration of the urine, neurological dysfunction, respiratory failure, jaundice, and sometimes presence of bleeding diathesis. Severe cases may lead to organ failure and death. However, some cases during the initial stages appear to be unnoticed to the pet owners. On the other hand, chronic stages often make the dog a carrier of the organism and become asymptomatic, and for how long a dog will be a carrier is unknown. Some dogs remain asymptomatic carriers of parasites, presenting high antibody titers for a period as long as one year. The asymptomatic infected animals facilitate the transmission of parasites to tick vectors. Dogs may develop clinical babesiosis several times during their lifetimes.

The diagnosis

Blood smear examination is a useful diagnostic tool for clinical babesiosis in dogs. Microscopy evaluation continues to be the easiest and most accessible diagnostic test for most veterinarians. However, the blood smear examination presents a low sensitivity in assisting the veterinarian in making a positive diagnosis. Serologic or antibody testing can confirm previous exposure to B. gibsoni. Antibody reaction to the B. gibsoni can be measured by ELISA in the lab, or by a lateral flow immunochromatographic test (or rapid test) in the clinic. This rapid test has been commonly assisting the veterinarians for fast diagnosis. A positive test result is dependent on an antibody response by the infected dog, which may take up to ten days to develop. Once a dog has developed antibodies to babesiosis, they may persist for years and this must be considered when performing follow-up tests. Molecular diagnostic assays (PCR or real-time quantitative PCR) have been widely used for the diagnosis of babesiosis. These molecular diagnostic methods have greatly increased the sensitivity and specificity of Babesia detection. The detection of DNA for a specific pathogen in a clinical setting can be considered evidence of an active – and therefore ongoing – infection.

The Treatment

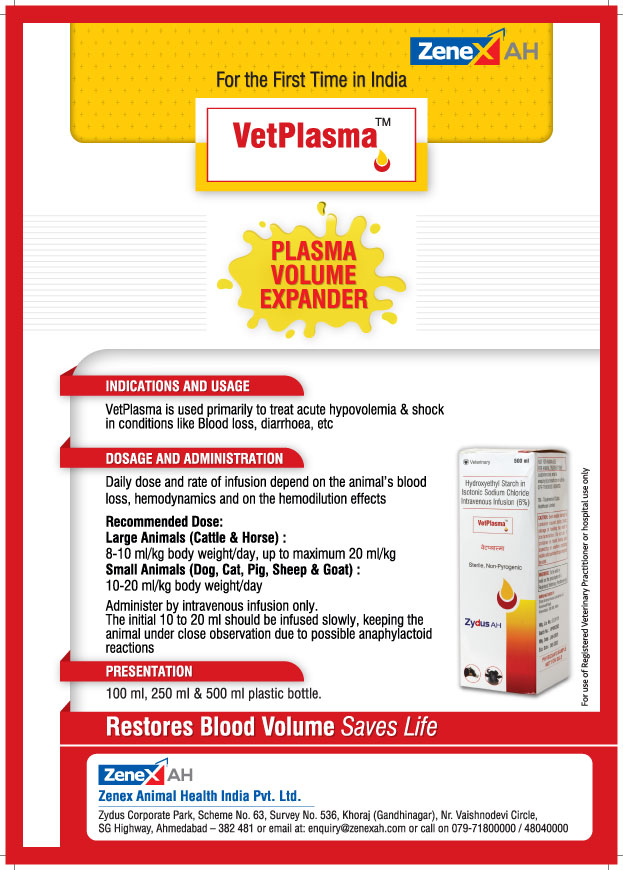

A combination therapy of azithromycin and atovaquonehas been widely applied to eliminate or suppress parasite numbers of B. gibsoni below detectable levels in the majority of dogs with no adverse reaction. Other optional treatment for dogs infected with for B. gibsoni is using triple antibiotic combinations of doxycycline, clindamycin, and metronidazole or combinations of doxycycline, enrofloxacin, and metronidazole. Supportive treatment is required for moderate to severe babesiosis, such as blood transfusions for severe anemia. PCR testing can be conducted to assess response to therapy, but serologic testing is not suited for this purpose.

The Re-infection

The same dog can be re-infected by identical Babesia species, including B. gibsoni, or coincidentally with a second species. Although the clinical consequences of re-infections are not well defined, in endemic regions, it is possible for dogs to be chronically infected, in a premunition phase, without clinical consequences; this phase may even be beneficial in terms of protecting against future infection.

The Prevention

Vaccines against B. gibsoni are currently being developed. The most effective preventive measure is avoiding exposure to the vector. This should be considered when deciding to take a dog from non-endemic into (highly) endemic areas. As a pet owner, regular control of the tick vectors by routinely dipping or spraying pets or using tick collars or spot-on preparations is the best way of preventing this disease. Regular examination of dogs to remove ticks soon after they attach is also important as it takes a minimum of 48 hours before Babesia transmission occurs. In addition, preventing dogfighting as well as direct blood contact by using sterilized instruments during tail docking and ear cropping procedures and when administering injections are critical. Good screening measures should be established for potential blood donors to prevent the disease from spreading.

" >

" >

" >

" >